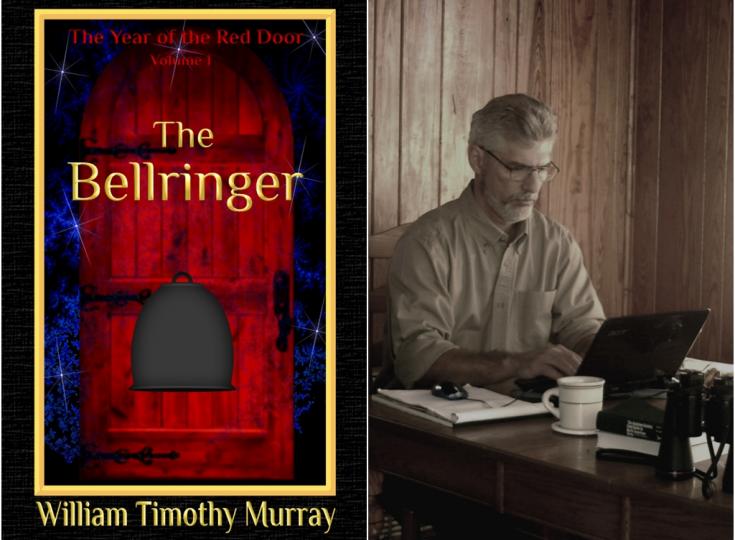

William Timothy Murray - Epic Fantasy with a Relatable Hero

William Timothy Murray was born and raised in a small town of the American Deep South and now lives in the Appalachian foothills of northeast Georgia. He enjoys stargazing, tinkering with an old sailboat, and listening to music. He keeps a small writing desk in an old barn. There, amid a clutter of maps, drawings, and books, his memories and experiences join with all the tales he has read to inform and disturb his pen. As our Author of the Day, Murray tells us all about his latest novel, The Bellringer.

Please give us a short introduction to what the Bellringer is about.

The Bellringer is about a seemingly ordinary young store clerk. Through an unusual turn of events, he learns that his mundane out-of-the-way existence is surrounded by secrets, mysteries, magic, and conspiracies. Just as he begins to come to grips with these revelations, his homeland is plunged into chaos with the arrival of conquering invaders. The desire to survive and to save his family and home forces him onto a path which will make him into a extraordinary king. The Bellringer is the first part of the five-part story The Year of the Red Door.

What inspired you to write a story about a humble clerk who becomes the most powerful king ever?

There were certain ideas and themes that I wanted to explore. Ideas about power, about loss and regret, and about finding forgiveness and redemption. And the more I worked on where I felt the story should go, the more it seemed appropriate to use well-known tropes and situations that are the fare of epic stories. There are many stories somewhat like this one, stories that come to from Classical Greece and Rome right up through the present day. Stories about ordinary people who discover special abilities are quite popular these days. So I guess you could say that I'm using a well-established story form that centers around some kind of quest. It seemed the best way to go. Besides, I've always loved good adventure stories, both fiction and nonfiction and so I wanted to write a story that I would love to read.

Why Fantasy? What drew you to the genre?

As a writer, I find that fantasy gives me a wide canvas to explore things through storytelling that might seem too outlandish to address in other genres. For example, The Year of the Red Door lets me share some ideas about immortality. Through the story I show that immortality as we normally think of it might not be all that it's cracked up to be. That's just one example. Like Science Fiction, Fantasy allows you to set up hypothetical circumstances, cultures, and worlds that most other genres do not allow. That kind of freedom makes it somewhat easier to challenge closely-held assumptions and beliefs, or to at least offer some alternative ways of thinking about things. Fantasy and Science Fiction are the ultimate "what if" genres, and there's no wonder that many stories in those genres have an allegorical tone.

You live in the Appalachian foothills - how does your environment inspire your work?

I don't think anyone who grew up as I did in the American South could avoid being exposed to a fair amount of storytelling. From a very early age I listened to the grownups sit around and swap all kinds of stories, ghost stories, stories about getting lost in the forest or being taken away by spooks and haints. Such stories were mixed in with tales about life and times from days gone by. So there's that aspect of things.

But the landscape itself, here in Georgia, is remarkable in its diversity and has been quite a inspiration. The small town and the surrounding county that is the main setting of The Bellringer is like the small town where I grew up, not too far from the sea, and not very far from the mountains. Like in the book, agriculture was the driving economic force surrounding the town. Most everyone had a sense that they knew everyone else, whether they did or not. And there were lots of forest lands for me to explore, deep shady places so wild and beautiful that it was easy for me to imagine that I was the first person ever to find them. In the mountains not far from where I live today, there are places that are still like that. If a figure stepped out from behind a tree, it could be a bear or an elf or a witch, and none of them would seem out of place.

Why, would you say, is the accidental hero so relatable to readers?

Robby Ribbon is ordinary in many ways. He's a good lad. He tries to be a good son to his parents, and a good friend to his chums. He's smart, but he's no genius. He works hard, and like many young men he secretly yearns for adventure. A lot of us can relate to that. Robby finds out the hard way that he really is special. That's something that we all want to believe about ourselves, isn't it? Robby finds out that he is destined for greatness, although when things start pushing him in that direction, he is not all that enthusiastic about it. He says that everything is just an accident, and he says that he's too ignorant for greatness. He is truly humble in that way.

Most of us tend to have a great opinion of ourselves. We tend to be quite confident. We overestimate our abilities, and underestimate our shortcomings. Robby is just the opposite. He underestimates his skills and his fortitude, which he has in abundance. But he is anything but confident, continually wracked with self-doubt. That makes him different. He does have a lot to learn, but so much of it is really just information. He already has an essential goodness, a maturity about him that no amount of learning can instill.

So I think we relate to Robby as a good person, the kind we want to be. And we relate to him in the sense that we want to be special, too. Really special, with a special destiny that nobody else can fulfill. But maybe we're also afraid of being special, afraid of what path being special might force us onto. That's just like Robby.

Besides writing, what other secret skills do you have?

Using only one hand, I can take a match from a book of matches and light it.

Does writing about surreal worlds and enigmatic scenes present any particular problems?

I'm often asked about Worldbuilding when it comes to writing fiction. And I've taught some workshops on it. Everyone has to develop their own approach, I suppose. But I think that the main thing is to be sure that all is done in service to the story that you have to tell. Wizards doing battle inside a glass bottle that's sitting on a shelf in a witch's cottage, is just cluttering things up unless it serves the story. Let's face it, life is complicated, mysterious, magical, and enigmatic all on its own even in the most mundane of circumstances. A little fantasy goes a long way.

You also included a pet or two in your book. Why?

Animals and their relationship to people are very important to the story. Some of the animals are actually magical creatures trapped inside animal form. They are called Familiars. As the tale progresses, we discover more about what makes Familiars so important. They are not pets in the ordinary sense of the term.

The Bellringer is the first book in a series. Did plan from a start to make this into a series? How does the next book in the series tie in with this one?

The Year of the Red Door is not a series in the sense that each instalment is relatively self-contained. Rather, it is one continuous story, a pentalogy. That is, it is told in five volumes. The Bellringer is the first volume, the opening act if you will, of this story. Each volume picks up where the previous one left off until the final volume To Touch a Dream, which concludes the story.

I wrote the whole thing, all five volumes, before publishing the first volume. I originally wanted to publish The Year of the Red Door as one single massive tome. But my wife prudently urged that I make each volume a separate publication. As it is, each volume is quite long as the story is dense and it is quite involved.

Do you have a set of rules for your world? Is there a process you go through that helps define these?

I don't have a set of rules, per se, for the world of The Year of the Red Door. Other than the need for internal consistency. The main consideration is to have a good history for this world. Nothing happens without some prior condition or cause, some bit of history behind it. And nothing epic happens without those prior causes also being epic in nature.

So I spent a lot of time during the writing making certain that this world and this story were in sync with each other. That meant asking myself a lot of questions, testing the structure behind the story. Questions like, "Why did the desert people call themselves the Dragonkind?" "How long does it take a person traveling on foot to reach the other side of the county?" Some of the answers required me to map out physical locations and routes. Other questions required me to develop some kind of backstory or history. My notes, as you might imagine, are quite extensive, full of events and characters that are not in the story at all. But they are the supporting history behind the story.

Do you have any interesting writing habits? What is an average writing day for you?

Writing is work. A kind of calling. Something that you ought not shirk if you know what's good for you. You do it even when you don't necessarily feel like it. You do it because not doing it is even worse than doing it when you don't feel well, or when you're just tired. At least that's how I feel about it.

I don't have any gimmicks or tricks or secrets when it comes down to it. I just write, and I strive to write every single day. I make sure that I have something to write on, a notebook or pad of paper, near at hand everywhere I go. I try to avoid being chained to technology—to electricity—so I don't wait until it is convenient to sit at my desk or to get out my laptop or phone. And I don't wait until I have a large block of time. That attitude, or that ethic, helped me write The Year of the Red Door because I was able to work on the story five minutes here, ten minutes there, whenever I had a few moments, wherever I found myself.

That said, my preferred writing time is at night. I'm something of a night person anyway, I guess. But I like to work in silence most of the time, and things are just quieter at night. Or, if I want to listen to music (and I do listen to a lot of music), it isn't to cover up other noises (which really doesn't work—more sound is just more sound). Another reason I like to work at night is that I like to step out and look at the night sky. It rejuvenates me and reminds me how small and temporary we are.

I do most of my work at a desk that I keep in an old barn a small distance from my house. I am often visited by various creatures. Owls, deer, rabbits and the like. The occasional fox. Well, they don't exactly visit me. I just see them as they pass by. Except the owls. They like to perch in the trees surrounding my barn and heckle me.

What was your greatest challenge when writing this book?

That is a really good question, but not one that's easy for me to answer. So much about this story was a challenge for me. One of the big challenges was that lot of the storytelling in The Bellringer was be like planting seeds. I had to plant the seed of an idea and move on. I knew that if I got it right, that seed would make what happens later on seem familiar or ring true, even if a reader can't put a finger on exactly why it seems familiar. Those seeds, those hints, really do prepare readers for what takes place later on in the story. But I had to be really careful about it.

For example, in the first chapter of The Bellringer, the main character, Robby, is asked by his father to lend a hand to open a jammed display case. Robby opens the case easily, and his father wonders out loud why he always has trouble opening that case but Robby never has trouble with it at all. This might seem a small thing, but it is the first hint of one of Robby's special abilities. It turns out that Robby has the uncanny ability to open any door, unlock any lock, loosen any knot, or free any chains that bind. That first hint is but one of a series of such hints pertaining to Robby's abilities, and it also foreshadows his destiny. He will be able to do what others have failed to do, or what others lack the skill to do.

Managing those kinds of hints and "seeds" without giving away too much too soon was a big challenge. I had to do a lot of rewriting in an effort to get that just right without being too obvious about it. For readers who might like a few more clues like that one, I'll just say keep an eye out for lockets, coins, sand, ink, and scars. All of those seemingly mundane things will come back around more than once. As The Year of the Door progresses, those things take on more importance each time they are mentioned.

What are you working on right now? Can you give our readers a sneak peek of what to expect?

I've got several writing projects going on, several irons in the fire, you might say. I don't know which, if any, might actually prove to be viable.

Where can our readers discover more of your work or interact with you?

There are a couple of good ways to learn more about me and to read more. The first is to go to my web site at www.TheYearOfTheRedDoor.com. The site is built for content, and there are stories, maps, chronologies, essays, and information about where to buy my books. I've tried to make the site responsive so that you can use it with your smartphone or tablet. The other way is learn more is to subscribe to my newsletter. That's where I share stories, answer reader questions, and pass along special freebies and discounts for my books. Anyone can join the list by going to the website and signing up there. That's at www.TheYearOfTheRedDoor.com.