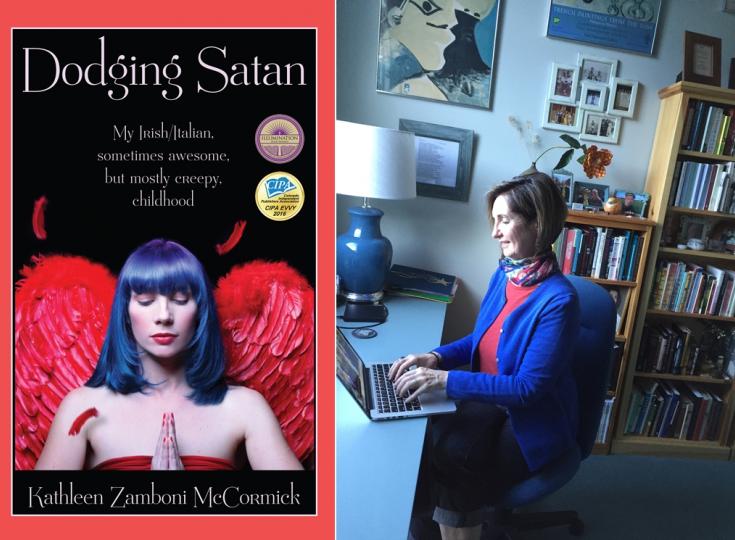

Kathleen McCormick - Infusing Religion, Sexuality and Imagination in a Humorous Coming of Age Story

Storytelling has been a part of Kathleen McCormick's life for as long as she could remember. As a child, she believed that stories had the power to keep people safe. Family gatherings were filled with stories, and every aspect of them enthralled her. Her own childhood and vivid imagination inspired her award-winning book Dodging Satan, a humorous coming of age story that explores religion, sexuality and family relationships. As our author of the day, McCormick reveals why she was ecstatic when she first discovered Bible stories, talks about her own childhood, Irish and Italian culture clashes and much more.

Please give us a short introduction to what Dodging Satan is all about.

Dodging Satan is a humorous but poignant coming-of-age story of Bridget Flaherty, a student at St. Michael’s Catholic school outside Boston in the 60s and 70s. The book opens with her having received a frightening ‘Godly gift’ for her first Holy Communion at age 7 and ends when she’s 14, a freshman in high school, devoted to the Virgin Mary, ‘even though she hasn’t gotten pregnant in high school.’ Bridget’s wacky misunderstandings of Bible Stories and Catholic beliefs enable her, for much of the book, to avoid the problems of her Irish/Italian family life. She creates glorious supernatural worlds—with exorcisms, bird relics, Virgin Martyrs, time travel, Biblical plagues, even the ‘holy’ in holy water!—to cope with a family where leather handbags and even garlic can cause terrible strife. It’s my hope that Bridget’s musings on sadistic nuns, domestic violence, emerging sexuality, and God the Father’s romantic life will both move and delight readers.

What inspired you to write a humorous coming-of-age story that deals with religion and sexuality?

My greatest inspiration to write is the power of laughter. My childhood has some parallels with Bridget’s, the main character of Dodging Satan, and, early in my life, I came to value anyone who could make me laugh because of the incredible feelings it created—release, joy, lightness of being. I’ve never stopped appreciating the power of the comic, and I get such pleasure when I make someone laugh, or even smile.

For as long as I can remember, I believed that stories had the power to kept people safe by somehow magically enveloping us. I’m also very interested in the ways in which children often misunderstand much of the information they are given, making it conform to their own worldview. Bridget’s misunderstandings—which no one but the reader is privy to—is what makes Dodging Satan humorous.

As a child, when I discovered Bible stories, I was ecstatic. Not only did they promise me a virtually endless source of interesting narratives, they were all somehow connected and connected to me. You could say that Bible stories were my first experience with a “series.” Harry Potter has, what, eight? Nancy Drew had 56. But the Bible! It had an Old Part and a New one, each made up of almost infinite sections. The main character was divided into three. How cool was that!

Further, because God was present in all places across time and space, I felt that he was responsible for everything in my immediate and extended family. It was a relief to think that all the tension, verbal, and physical abuse that happened in my personal life was ultimately of God’s making, that everyone was somehow doing his will. Some Amazon reader comments on Dodging Satan suggest that religion is the source of most of Bridget’s difficulties—and of course in a humorous book, it’s impossible not to have a few nasty nuns in there.

But as I remember my life as a child—and I feel this is true for Bridget as well—religion made frightening experiences not only endurable but epic. It was such a relief to believe that my every experience was part of a grand plan that God was controlling, particularly when my life and the key people in it seemed so out of control. If my parents had an argument, it was God’s doing. When I felt afraid of the dark—like most children do—it was Satan, haunting my bedroom and filling it with plagues and pestilences from the Old Testament. Scary, yes, but epic, as well!

The book is about religion and many aspects of a child growing into her teens, so naturally, sexuality is going to get in there. And as Bridget’s Catholic friend, Agnes, points out, how can we mortals have sexual feelings if God didn’t have them first, hence Agnes and Bridget’s speculation on God-the-Father’s romantic life.

How much has your own childhood influenced this book?

I am not Bridget, but Bridget is most definitely mine.

At home, alone in my tense nuclear family, any lack of storytelling seemed to me potentially quite dangerous. So at an early age, I began to fill the gaps with as many stories as I could create, treading a fine line between embellishment and truth, and always searching for ways to be amusing and, in retrospect, a little weird, in order to mollify, to sooth the pain my parents seemed unable to stop causing each other.

I interpreted the whole concept of immanentism in Catholicism to mean that God was always on hand to have a conversation with. For a long time, I found that extremely comforting, as does Bridget, whose experience of God is much more off-hand than mine was, which I hope adds to the humor: “‘Did you have any idea she’s a model?’ [Bridget asks God about a first grade classmate she's about to perform an exorcism on.] God answers immediately. ‘Of course, my child, I am all-knowing.’”

Exaggeration and a touch of the weird were probably the most consistent elements in the stories I told as a child. And to this day, I exaggerate when I tell a story—it happens without my volition. “About 80” is code my husband laughingly uses whenever I exaggerate. Roughly translated, it means that I could say “about 80” when an actual number in a story I’m telling is probably closer to five or twenty.

So the propensity to exaggerate, embracing the slightly weird, and being comical are all attributes Bridget shares with me. And, as I said above, I love to make people laugh. I really do believe that laughter is such a gift. This is something I had a field day with in Dodging Satan—I very consciously exaggerated bits of “real life” story and then created other stories in which it would be quite obvious that Bridget is exaggerating—to everyone but Bridget—which is part of the fun of the book. I’m so pleased when I read customer reviews on Amazon from people who say they laughed out loud when reading Dodging Satan. I’m also happy when they say it’s a little weird. I’m thrilled to have that connection with my readers.

Some of the events in Dodging Satan did really happen to me. For example, my mother and I opened a nearly empty Holy Water container, but with much less drama than Bridget and her mom. And I really thought I saw “the Holy” in it. Only later did I realize it was something totally different. But how much more exciting to believe I’d been allowed to glimpse “the Holy.” And what a better story!

Bridget is wrestling with how God and men treat women. Why was this an important theme for you to explore through your book?

Physical and verbal abuse of women by men is as much a problem today as it was in the 60s and 70s when the story was set. Only today it’s somewhat more open. And certainly, misogyny is particularly alive and well in our country at the moment. If one studies the history of how the Bible was created, you can actually trace ways in which strong women were written out and misogynist views were promulgated. Feminist theologians at the time Dodging Satan is set were beginning to articulate how Catholicism and the Bible reinforced misogyny among believers, perhaps unconsciously. Obviously, Bridget is too young to be aware that formal feminist critiques of religion were going on (but she won’t be in the sequel!), and many people today who don’t study theology aren’t consciously aware of them.

I’m not saying that Catholicism was responsible for the mistreatment of women at the hands of men, but it didn’t discourage such treatment. Bridget’s a smart girl and the links she makes between God-the-Father and her verbally abusive father and physically abusive uncles, though naïve, do heighten an awareness—in their own particular bizarre idiom—of a potential connection between the two.

Tell us more about Bridget. Who is she and what makes her so special?

Bridget is precocious and has obviously—despite the number of ‘family secrets’ in her household—been given way too much information for a child at any of the stages of her life the book covers. What makes Bridget so special and endearing is that she always comes up with a way to make sense of what she has read or has been told. And she is always mistaken in her conclusions.

For example, she believes that the reason mosquitoes and other nasty stinging insects exist in the world is because when Noah was building his arc, he went mad from lack of sleep because of the pressure of having to complete his task in only ‘40 days and 40 nights.’ So Bridget believes that while Noah saved a lot of wonderful animals, he then chose to also save annoying insects that to her would have been better left behind. She speculates on the possibly wonderful animals that we lost because God set Noah an unrealistic deadline which caused him to bring mosquitoes rather than possibly rainbow colored cat-like creatures. Bridget is obviously projecting her own anxiety about pressures she feels at home and in school onto Noah, but only the reader knows this. No one in her family has any idea of her bizarre interpretations of bible stories or that she thinks that she and God can carry on active conversations.

Bridget also asks questions that I think a number of believers would ask, but her child-mind comes up with unusual answers. I mean, really, if the Garden of Eden was actually Paradise, what was that snake doing there (another ‘animal’ that Noah would have done well to leave behind)? Anyone, from ‘parish Catholics’ to theologians, has a variety of answers to this question. And Bridget has her own answer: influenced by the fact that her best friend, Agnes, has recently discovered and read a hoard of her mother’s romance novels, Bridget imagines that the snake is in Paradise because God-the-Father is caught in a love triangle. This may sound crazy, but it has a special Bridget-logic of its own. For more particulars, I recommend you read the book!

Dodging Satan finds a lot of comedy in theology, while at the same time taking religion seriously. How did you pull this off?

Two different critical reviews of Dodging Satan comment on the book’s use of what Andrew Greeley calls the ‘Catholic imagination,’ the belief in “a God who is present in the world, disclosing Himself in and through creation,” what I refer to above as immanentism. In Dodging Satan, I try to take to an extreme what the effects of such a belief in God’s physical presence in the world might be to a child with a particularly active imagination.

So when Bridget muses on the Incarnation, the “word made flesh,” she worries how a very human, very young woman would have actually dealt with raising a child who was one of the three persons of the Holy Trinity: “I mean, you have a baby and it turns out to be God. Where does that leave her? She can’t even discipline Him. And talk about on-demand feeding. He’s God, for heaven’s sake. What He wants, He has to be given.”

Bridget’s unintentional irreverence occurs repeatedly, when she worries whether breaking a cheap school rosary is a sign of the precarious state of her own soul, or when she obsessively imagines the exact crucifix she wants for her First Communion: “authentic-detailed,” bloody, and violent, so that “just looking at it gives you the feeling that you went through the whole fourteen Stations of the Cross.” Bridget is disappointed to actually receive “a thin, almost transparent white plastic crucifix on a tiny matching round stand—it couldn’t even hang—with a puny silver Jesus on it.” Satan isn’t a myth for Bridget; he haunts her bedroom every night. Mary isn’t a figure from the distant past; “she gets to time-travel and become famous across all time and space.”

I hope to show in Dodging Satan how Catholicism can be a religion of living and frightening presence, particularly to a child. The humor derives from the combination of Bridget’s limitations—she can only comprehend the complexities of the eternal with her extremely literal child-mind—and her absolute assuredness that she’s figured it all out.

The clash between the Irish and Italian cultures also play a prominent role in your book. Why?

The short answer is: ask any Irish-Italian American! I recently was part of a local book fair that had been written up in our local newspaper. A number of people had read descriptions of my book in the paper and many of them came up to my booth, looked at me, checked that I was “the Irish-Italian one” and just started laughing. We didn’t have to say a word and they bought one or more copies of Dodging Satan!

Here is a longer, more serious answer: After decades of antagonism in America, after World War II, children of Italian and Irish immigrants began to intermarry. So since large numbers of people in the US share Irish and Italian ancestry, one can too easily forget the hostility that previously existed between Italian Americans and Irish Americans. I grew up with my Italian grandparents and my Irish grandfather expressing this hostility. “The Catholic church was taken over by the Irish and wasn’t worth attending.” Many Irish, who immigrated slightly earlier, felt that Italians coming to the US in the 1880s were “too inferior” to become “Americans.” All of this is well-documented in American history.

Perhaps the best known recent representation of Italian-Irish tension exists the film version of Colm Tóibín’s book, Brooklyn. I’ve done research and written on the status of Italian Americans in this country, but what made the tension play such a prominent role in Dodging Satan for me is that Italian/Irish tensions were the first ethnic antagonisms I experienced as a child. And, like most prejudices, they didn’t seem based on anything real. My grandfather called all Italians “low class,” but he was much poorer than my Italian grandparents. I couldn’t understand how or why my mother forbade me to tell anyone in our Irish parish when I started to go to school that she was Italian.

Obviously prejudices against new immigrants exist to the present day, as has become increasingly obvious in the last month, and similarly, these prejudices often exist without any basis in the real.

Besides writing, what other secret skills do you have?

I always say that if I hadn’t been allowed to go to college, I’d have become a weaver. I love doing anything with a needle and with thread or yarn, whether it’s sewing, knitting, crocheting, crewel work, you name it. I did a lot of needlework with my mother growing up and those times when we were making something together seemed insulated from the tensions of our lives and as safe as a story. I don’t get to do nearly as much needlework as I’d like because I’m a Professor at SUNY, Purchase—and I love teaching my students who are usually my number one priority. My mother also tried to teach me to bake, but with less success. It’s taken my interest in Paleo eating to get me to start cooking more seriously only quite recently. But I now make a chocolate chip cookie that I’d challenge anyone to beat in a bake off!

You know exactly how to bring your characters to life. How do you create such relatable characters?

Storytelling has been a part of me for as long as I remember. Family gatherings were filled with stories, and every aspect of them enthralled me. I’d listen for different cadences, distinct rhythms of each relative, admiring the wealth of styles they’d use to make even the drunkest among us grow silent. Captivated by the undulation of their voices, how they might whisper in cigarette-husky tones, how their pitch could deepen here, rise there, how they could hold us, rapt, or, in an instant, make the room and any strains within it dissolve in laughter.

I love to listen to how people tell stories and obviously as a College Professor of Literature, I love to read stories.

So for me, listening and reading, and never taking myself or my characters too seriously is what I think makes them real and such fun to write into existence.

Did you always know you wanted to be an author?

I’ve felt compelled to write for a very long time. Writing is simply something I have to do. For many years, my writing was exclusively academic—about literature, or about teaching literature or teaching writing—and I found that incredibly stimulating. For the last decade or so, I’ve done more “creative” writing, though, of course, academic writing involves great creativity. I want to write because I love the process of writing, the sense of discovery that accompanies it—you never end up where you think you’re going to—whether you’re writing a story or a critical analysis of something.

But I didn’t always want to write. A cousin of mine had a nervous breakdown at the age of 12, obviously because of all the domestic violence he’d witnessed growing up. But in our family lore, as bizarre as it sounds, his breakdown was attributed to the fact that he was allowed to read and write before he went to school—that he somehow strained his brain at an early age and that this had long-term consequences. (I’m sure you’re going to stop wondering about the weird in my stories!)

So I was forbidden to try to read on my own or to write more than scribbles until I went to school. The first story I recall writing—because it resulted in required visits by both of my parents to some of the nuns—was for an in-class assignment. The subject was what we were going to be when we grew up. With great detail—I know because this story was saved for years and frequently brought out by my parents—I wrote about how I was going to become a wife and mother. I focused particularly on my children, a boy and a girl, and how they would create a beautiful garden with me which we would tend constantly and how they would love going to Catholic school and coming home and eating cookies that I’d just baked for them.

In a rather progressive move, the nuns called my parents in for a conference. Apparently, I not only wrote the longest and most elaborate story in the class, but I was the only child—boy or girl—who didn’t imagine that I’d have some profession outside the home—hairdresser, policeman, astronaut—when I grew up. At this conference, my parents were also informed that I was actually quite intelligent and that the nuns expected them to increase my aspirations.

The conference caused mixed reactions in my parents and a fear in me that writing stories could quite unwittingly get a person into trouble. My parents were annoyed to have discovered from “an outsider” that I was smart. Why hadn’t I told them myself, they asked me accusingly? Somehow saying, “Because I didn’t know,” sounded pretty inadequate. Surely someone supposedly intelligent would realize she was. My parents acted as if I’d been intentionally keeping a big secret from them—a real taboo in our household.

When confronted by an angry father demanding to know what I really wanted to become and a mother upset that the whole notion of my wanting to be like her (except with an extra child) apparently now wasn’t good enough for anyone, I remember saying that I was going to become a nun. It was the first thing that came to mind—I had little experience with women working outside the home. This resulted in my mother running from the room in tears and a fantasy that I’d return to for many years, and always, as in this instance, for the wrong reasons.

So it took some time before I wrote or wanted to write other stories. I became a firm believer in the oral tradition since the written word—or my clumsily formed written words—could cause so much consternation.

If you could have a drink with anybody, living or dead, who would it be, what would you have and what would the discussion be about?

I’d like to have a drink with James Joyce. (I’d pay for the drinks because he wouldn’t have the money.) We’d be in Paris and would talk about literary style and Catholicism, the second of which he’d say he wasn’t going to talk about, had moved beyond, but it would infuse everything he said. (I wouldn’t ask for him to sign my 20-year-old marked up copy of Ulysses.) He would just know that next to Shakespeare, he’s the most written about author in the English language.

When I first read the bits of James Joyce’s Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man that I could understand while in high school (I came upon Joyce in a used bookstore; he certainly wasn’t assigned reading in my Catholic school!), I experienced such an incredible sense of hope. Someone—who was filed under “Literary Classics,” who was not only Irish, but an Irish tenor—had grown up in an environment of alcoholism and Catholicism, in a city of domestic abuse, and was deeply critical of the Catholic faith, but yet still seemed totally engulfed by it.

Joyce, in my desperately superficial reading of him then, wrote about characters who seemed to be stuck in the same way I was. We felt an urgent need to get out of the parish, maybe out of the Church, definitely away from home, and as well had an acute fear of leaving. Joyce was a lifeline for me well before I realized that he’s one of the greatest writers in the English language.

Today, I’m the resident Joycean in the college where I teach. I’ve written a couple of books and some articles on Joyce, but no one knows that I had this early, kind of primal, and a little embarrassing, connection to him. I wouldn’t mention it in the conversation I’d have over drink with Joyce, though he’d immediately know.

Tell us a bit about your writing habits. Do you prefer pen/computer, morning or evening, have a favorite writing spot?

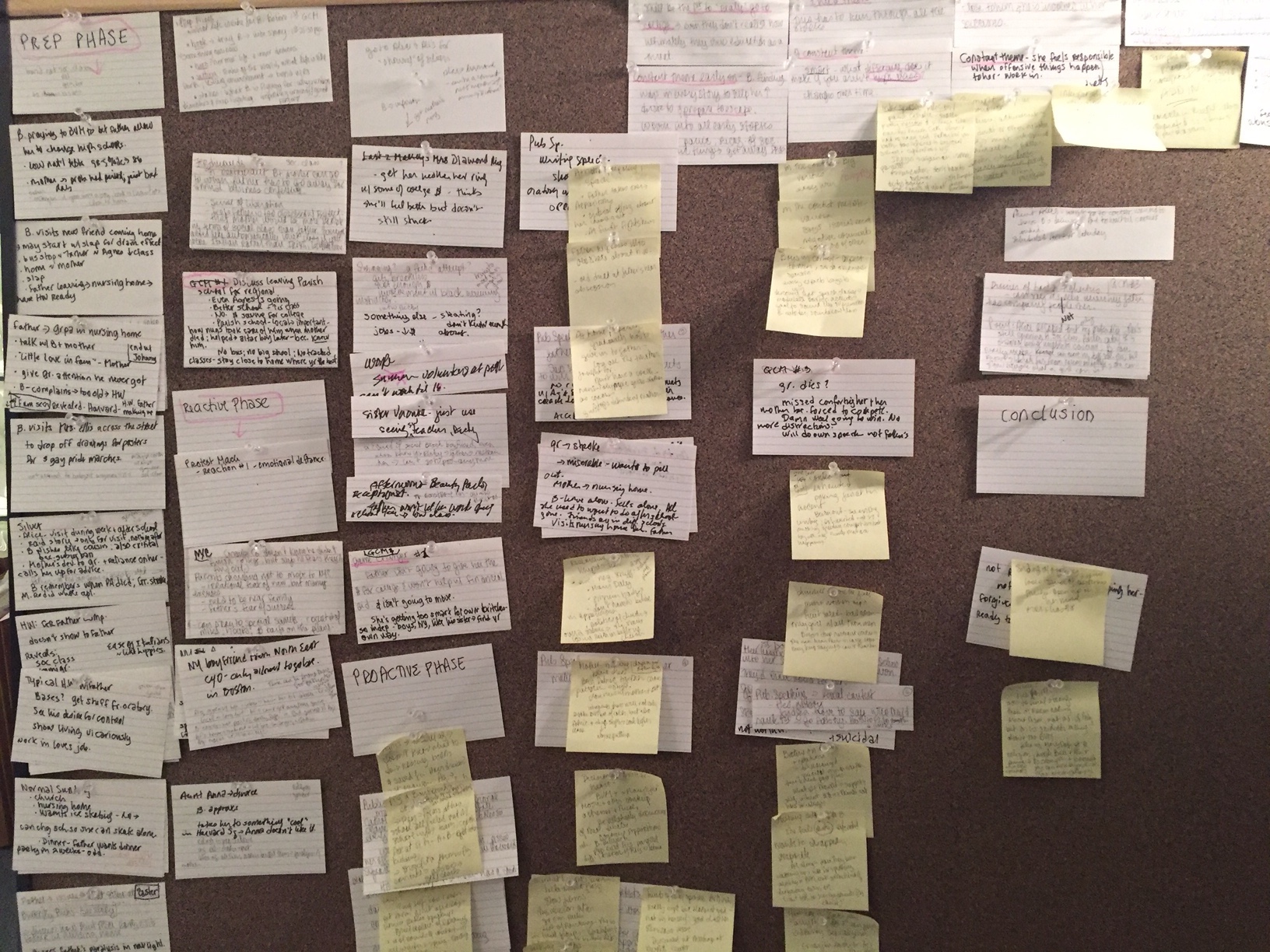

We recently moved into a new townhouse that has an incredibly cool room at the top, where my 15-year-old cat, Katerina Puck, and I hang out to work. I call it our “chick loft” and it’s got my huge storyboard in it where I plot out my work by hand on index cards, a sloping ceiling under which I write on my laptop, and an incredibly funky window that lets me look at the world outside to see if it’s more interesting than the world developing in the loft. I like to get a couple of hours of writing in during the morning, which sets the tone for the work I’ll be doing the rest of the day (if I’m not teaching!)—researching, revising, brainstorming, or more new writing.

Who are the authors you’d be found reading?

Ali Smith, especially How to be Both. Marisha Pessl, especially Special Topics in Calamity Physics. Though such different types of writers, they both do weird particularly well. And, of course, like the rest of America, I’m in love with George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo, and he’s coming to do a reading at my college in a couple of weeks which I’m incredibly excited for.

What awards has your book won?

Dodging Satan just won a 2017 Illumination Book Award in the category of Catholic Books. This was particularly exciting because while I won the Bronze Medal, Pope Francis won the Gold. I’ll be happy to take the Bronze to the Pope’s Gold any day!

The book has also won two Colorado Independent Publishers Association, 2016 EVVY Awards: Gold Medal for Religion & Spirituality; Silver Medal for Humor, August 2016.

What are you working on right now?

I’m writing a sequel to Dodging Satan which focuses on Bridget’s final two years in her same Catholic high school. Cambridge, MA, where Bridget lives, has become increasingly hip during the 1970s and once again it is with humor and some pain that Bridget struggles to grow into the exciting and liberating new world she’s encountering. Whether discovering politics in protest marches and songs, feminism on the Mary Tyler Moore show, or shocking critiques of Catholicism in radical theology, Bridget feels increasingly constrained by her family. They seem paralyzed by their social class, endless family secrets (yes, there are many more than those in Dodging Satan!), ethnic tensions, sexism, and religious conservatism and Bridget must try to develop the inner strength to face those paralyzing forces and find independence without losing her family, social roots and religion.

Where can our readers discover more of your work or interact with you?

Readers can message me and read some of my work on my website, http://www.kathleenzmccormick.com/,

on my Facebook author page, https://www.facebook.com/kathleenzmccormick/, or

at my Amazon author page at https://www.amazon.com/author/kathleenzmccormick.

I’m available to meet with book clubs or do readings.