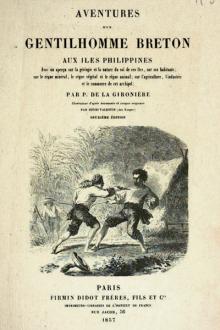

Aventures d'un Gentilhomme Breton aux iles Philippines

Aventures d'un Gentilhomme Breton aux iles Philippines

Book Excerpt

ouleuse; de grosses lames ballottaient la Victorine comme un simple esquif.

Ce mouvement que j'éprouvais pour la première fois me produisit bien vite les symptômes avant-coureurs du mal de mer. Je commençais déjà à éprouver de véritables souffrances, lorsque le lieutenant du navire, homme d'un caractère facétieux, m'adressa la parole:

«Docteur, me dit-il, vous commencez à pâlir; dans quelques minutes vous donnerez à manger aux poissons. Mais que faites-vous donc de votre science et de votre pharmacie? C'est pourtant le moment d'en user. Vous autres, savants docteurs, vous ne comprenez rien au mal de mer. Ce n'est pas comme nous, vieux marins, qui avons l'expérience. Si je voulais, pourvu que vous eussiez un peu de courage, sans aucun médicament, dans deux ou trois heures, je pourrais vous guérir.»

Je ne me doutais pas du plaisir que prennent les vieux m

FREE EBOOKS AND DEALS

(view all)Popular books in Adventure, Travel, Non-fiction, History

Readers reviews

3.0

LoginSign up

For historians, Gironiere’s writings are prickly, problematic sources. Of all the travel narratives written in the Philippines in the nineteenth century, his account was based on the most time spent there. Gironiere lived in the rural Philippines for twenty years from 1819 to 1839, the owner of a plantation on a Laguna peninsula known as Jalajala. His work is regarded as an excellent source on the cholera epidemic of 1820 and the massacre of the French residents, who were blamed by indios for the outbreak. The cholera riots provoked fears of revolution among the Spanish authorities in the wake of events in Mexico. As Gironiere is a source of much unique information, it is necessary to investigate his credibility.

Gironiere claims in the preface to his work that he was inspired to write his own version of events when he read a feuilleton by Alexandre Dumas Père in Le Constitutionelle. This feuilleton was subsequently published as Les Mille et un Fantomes. Dumas’ novel was a mélange of material: several lengthy and unconnected narratives, a memoir of one of Dumas’ recently deceased friends, and a story entitled Les marriages de pere Olifus. Les marriages told of M. Olifus, who, pursued by his mermaid wife, journeys to Bidondo (sic) and meets a Chinese woman, Vanly Tching, whom he marries. He then travels to Halahala (sic) where he converses with M. de la Geronniere (sic).

In the late 1840’s Gironiere had been holding forth in the salons of Nantes, regaling audiences with his tales of adventure in the Philippines and word of his stories reached the intellectually omnivorous Dumas. Stories of banditry were regarded as romantic and were wildly popular in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, and Gironiere told many bandit stories. Stumbling upon himself as a character in Le Constitutionelle, Gironiere wrote to Dumas and offered to sell his own story for publication in Dumas’ new journal, Le Mousquetaire.

Europe had just been rocked by a series of working class revolutions and their bloody suppression by governments. A marked shift occured in Dumas’ writing. An author who previously wrote romanticized yet trenchantly political stories, in historical settings which were but lightly fictionalized, Dumas now wrote a volume of fantasy with ghosts and mermaids and a journey to the exotic orient. The culmination of this journey into unreality is the encounter with ‘Geronniere.’

The revolutions of 1848-49 saw the rise of realism in art; for Dumas, they marked a flight from reality. His later work served as the inspiration for Hoffmann’s Nutcracker. There was nothing innocent in this literary choice by Dumas; he dedicated Les Milles et un Fantomes to the Orleans dynasty.

Thus, Dumas made a shift in his writing to fantasy and Gironiere’s salon fabrications provided the content of that fantasy for him. Gironiere’s work told how he single-handedly stopped a war, visited cannibals and headhunters and ate brains with them, and, above all, how he constantly encountered, captured, and conversed with bandits.

While Gironiere was waiting for his stories to be published in Le Mousquetaire, he tried getting them published elsewhere. He published his adventures as Vingt Années in 1853. He revised this slightly and republished it as L’ Aventures d’un Breton in 1855, adding an appendix.

Much additional information on Gironiere and his role in Philippine historiography is available at josephscalice.com

Gironiere claims in the preface to his work that he was inspired to write his own version of events when he read a feuilleton by Alexandre Dumas Père in Le Constitutionelle. This feuilleton was subsequently published as Les Mille et un Fantomes. Dumas’ novel was a mélange of material: several lengthy and unconnected narratives, a memoir of one of Dumas’ recently deceased friends, and a story entitled Les marriages de pere Olifus. Les marriages told of M. Olifus, who, pursued by his mermaid wife, journeys to Bidondo (sic) and meets a Chinese woman, Vanly Tching, whom he marries. He then travels to Halahala (sic) where he converses with M. de la Geronniere (sic).

In the late 1840’s Gironiere had been holding forth in the salons of Nantes, regaling audiences with his tales of adventure in the Philippines and word of his stories reached the intellectually omnivorous Dumas. Stories of banditry were regarded as romantic and were wildly popular in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century, and Gironiere told many bandit stories. Stumbling upon himself as a character in Le Constitutionelle, Gironiere wrote to Dumas and offered to sell his own story for publication in Dumas’ new journal, Le Mousquetaire.

Europe had just been rocked by a series of working class revolutions and their bloody suppression by governments. A marked shift occured in Dumas’ writing. An author who previously wrote romanticized yet trenchantly political stories, in historical settings which were but lightly fictionalized, Dumas now wrote a volume of fantasy with ghosts and mermaids and a journey to the exotic orient. The culmination of this journey into unreality is the encounter with ‘Geronniere.’

The revolutions of 1848-49 saw the rise of realism in art; for Dumas, they marked a flight from reality. His later work served as the inspiration for Hoffmann’s Nutcracker. There was nothing innocent in this literary choice by Dumas; he dedicated Les Milles et un Fantomes to the Orleans dynasty.

Thus, Dumas made a shift in his writing to fantasy and Gironiere’s salon fabrications provided the content of that fantasy for him. Gironiere’s work told how he single-handedly stopped a war, visited cannibals and headhunters and ate brains with them, and, above all, how he constantly encountered, captured, and conversed with bandits.

While Gironiere was waiting for his stories to be published in Le Mousquetaire, he tried getting them published elsewhere. He published his adventures as Vingt Années in 1853. He revised this slightly and republished it as L’ Aventures d’un Breton in 1855, adding an appendix.

Much additional information on Gironiere and his role in Philippine historiography is available at josephscalice.com

- Upvote (0)

- Downvote (0)

Free Download

Free Download